Author Archive

EMcounting the Mela: From Chennai to Prayag *

* With apologies to Prof Eck 🙂

This blog marks the final series of posts from the FXB Center Public Health team. It explains in some detail how the disease surveillance project was implemented and focuses on our local team composition. Subsequent posts will shed light on the water-sanitation components, and on our observations during the stampedes.

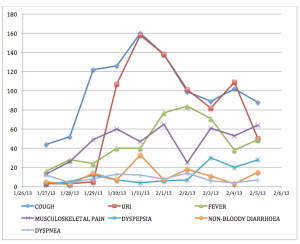

Yesterday, our team crossed the 30,000 mark. Since January 27th, 2013, the four sector hospitals that we have been following have seen over 30,000 patients. The hospital in Sector 11 has seen four times as many patients as that in sector 4. Upper respiratory complaints continue to dominate the presentation to the clinics (about 32%), with fever and musculoskeletal pain close behind. Over 58% of the medications dispensed were analgesics (pain medications) and a quarter were anti-histamines, all of which are available over the counter, without requiring the presence of a physician.

(FXB / EMcounter Team consolidating a long day’s work)

As we have repeatedly said on this blog, the political will and commitment to making the Mela a success is unprecedented, yet the staggering crowds that come to the Mela repeatedly overwhelm the system: the 30-120 second window for doctor-patient interaction, as the current data reveals, is far from the ideal that the Mela authorities had aspired to.

The size of this dataset will allow the authorities to examine several seminal issues surrounding healthcare delivery: prescription practice, resource allocation, epidemiology, and patient behavior at the sector hospitals in the Mela. Our analysis will hopefully influence planning and resource allocation for future Melas. Furthermore, having successfully demonstrated that it is indeed possible to collect such large quantities of data in this chaotic environment, we hope to work with the National Disaster Management Authority of India to consider piloting digital data collection in future mass gatherings in India.

As Dhruv points out, “quality data fosters accountability.” And quality data will help local authorities explore a whole range of new possibilities: engaging more mid-level providers and junior practitioners to see the large volume of patients, reserving the physicians’ time for the more acute cases; piloting cleaner cooking measures, educating the pilgrims on clean water, sanitation, hygiene.

Soon we will bring our surveillance at the sector hospitals to a close, but before we do that, we wanted to share the story of our team with you: the story of 20 public health and medical students from Allahabad and Mumbai who, armed with a handful of iPads, two mobile hotspots, five broken rental bikes, one portion innovation, two portions gumption, and a diehard commitment, logged over 1800 hours of work in 20 days to help this team achieve its goals.

The tool we used to log data is called “EMcounter” – it was originally developed by emergency medicine residents at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital (NYP) in 2006 to “count” the medical emergencies that presented to casualty wards of hospitals in India that were moving away from traditional one room receiving rooms to more sophisticated emergency departments staffed by trained emergency physicians. After its initial successful run at Sundaram Medical Foundation in Chennai, in 2007, EMcounter stayed dormant for a few years until a mobile tablet-based version was tested in South Sudan in 2012. EMcounter now had the capacity to collect data off-line on mobile devices, and could also analyze raw data in real time, as soon as it was uploaded. In other words, we needed several iPads to digitize the records at the sector hospitals, and mobile hotspots to guarantee generous internet availability to the data collectors. Both easily acquirable. Indian companies rent iPads, and mobile hotspots are an inexpensive investment.

What we needed was the official nod to collect this data, and an army of field staff to digitize the patient records. The National Disaster Management Authority of India provided the former and good Kumbh Mela karma the latter. Namita introduced us to Nutan Maurya, who had already been working with the other Harvard teams. As early as December, Nutan had lined up students from Allahabad’s Sam Higginbottom Institute of Agriculture Technology and Sciences. The Agriculture Institute (as it was formerly known) offers India’s oldest two-year Masters in Public Health. The MPH students were eager, sincere, and ready to roll. Senior specialists from NDMA, Naghma Firdaus, helped us identify a contact person in the Allahabad Medical College – Dr. Shraddha Dwivedi, also superintendent of Allahabad’s largest public hospital, Swaroop Rani Nehra Hospital. Dr. Shraddha Dwivedi who extended this team her enthusiastic and whole hearted support, made available a steady stream of rotating medical interns to augment this team. FXB Team 1: Dr. Gregg Greenough, Dr. Pooja Agarwal, and Neil Murthy laid the foundation for the successful implementation of this project during their stay at the Mela in January.

(Sam Higginbbottom Public Health Team)

(Allahabad Medical College Team)

Initially we wanted to cover all 10 sector hospitals and build some redundancy into the staffing. We were looking for more field researchers. Like our Allahabad group, future team members needed to be familiar with medical jargon, the public sector healthcare system, bilingual, and at ease negotiating the potential morass of bureaucratic red tape and obstructionism they may encounter. By then we had already made several trips back and forth between various authorities all of whom supported the project and all of whom were unable to provide us the requisite permission, until the NDMA stepped in.

Over serendipitous chai in the home of a loving Parsi family in South Mumbai, in an old house overlooking Marline Lines and Saifi Hospital, during a sort-of reunion of the Rotaract Club of the Caduceus, five medical students from Maharashtra thought it worth their while to commit their time and resources to spend two weeks at the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad. The Rotaract Club of the Caduceus, of which I was also once a member, was started in 1997 as a non-governmental organization committed to community service. What started as a motely group of 15 medical students is now a bustling organization of over 120, that conducts cataract camps, large fund-raising drives, and sometimes launches a nation-wide campaign to recruit student volunteers to conduct research in the world’s largest gathering. Panjak Jethwani and Ahmed Shaikh assembled two impressive teams of medical students from Mumbai, Nagpur and Allahabad, after vetting applications from across India and Nepal.

Our team was now almost ready. There was one missing ingredient. Aaron Heerboth.

India Today has written about Aaron’s exercise routine at the Mela and German television has done a segment on Aaron given instructions to the local team. Aaron is a graduating medical student from Weill Cornell Medical College, soon to begin his post graduate training as an emergency physician. He is also almost a Kalpavasi! Aaron is certainly Harvard’s longest resident member at the Nagri. Having arrived with the initial team in January, by the time the second public health team reached the Mela in early February, Aaron had consolidated his daily routine at the Mela: it involved running long distances between the sector hospitals, dodging cows, crowd and sadhus, jumping over grey-water ditches and steering his moped away from the slushy mud that collects at the edges of the metal plates lining the Mela roads.

By February we had realized that the large numbers of patients presenting at the clinics everyday would make it impossible for us to cover all ten clinics. We simply did not have the manpower to do that. We chose instead to pick four representative hospitals based on their diversity of location, accessibility and patient volume. Teams of two, three or sometimes four field staff were required to collect data at these centers. And every day, the overworked Mela physicians had to be gently reminded the importance of documenting at least the chief complaint and the medication dispensed. That was the limit of the medical chart. To expect anything more was foolhardy – given the few seconds that the physicians had per patient encounter it was no surprise that more could not be recorded. Interpreting handwriting, chasing down missing registers, drawing vertical columns in the ledger books and motivating the field researchers every day, sometimes several times a day constituted Aaron’s morning routine.

(Patient register before transcription to EMcounter)

Here are excerpts from Aaron’s notes to us:

“After somewhat clumsily navigating Allahabad’s shared rickshaw system this morning (which involved several transfers and numerous price negotiations) and a good 3 KM run through crowds of Sadhus, I arrived on site at sector 4 just after 9am to meet our eager public health students.

It appears that today we continue to be (somewhat) reliably up and running with Kumbh Mela EMcounter! Through numerous polite discussions, we have resolved some major physician handwriting issues at sectors 4 and 13, and our four public health students stationed at those hospitals are not having any significant problems. However, one team of two people with one iPad seems somewhat inadequate for sector 4 if we don’t want to overburden our data collectors. Sector 4, however, is on the main road to the Sangam, and has been seeing about 700 patients per day. Hopefully with the arrival of the Mumbai reinforcements, we can have more iPads and people at this site. I also think that at all sites, a larger show of presence will help motivate the physicians to document better records.

At 10:30 I had another Sadhu-dodging run to meet up with the medical interns covering sites X and Y. Things also appear to be going quite smoothly there. Unfortunately, at sector X the physicians are refusing to record chief complaint/diagnosis. I spoke to the physician in charge and tried to explain the big picture importance of recording this data (and I also mentioned that his superiors request it), and he seems to understand, but we will see where this goes.

Logistics summary for today:

Sector 11: Approximately 300 patients, all recorded. Started out with two iPads and 4 people and finished entering the 300 patients in about two hours.

Sector 13: Approximately 350 patients, half recorded wanted them to start fresh today but this was a miscommunication. They should be able to cover all patients from now on. I do feel bad because I very rarely make it to that site given that it’s about 4 km from the others. I did run there once today to thank the physicians for working well with our team.”

Aaron’s run through the Mela starting assuming legendary proportions – a news article mentioned it, bloggers blogged about it, and a satirical piece even disparaged it. Another few weeks and Aaron would soon become the “Running Baba”

Aaron reported on the Mumbai team’s arrival: “Today was our first day in the field with the new Mumbai students as well as our first day with a fresh batch of Allahabad students. The Mumbai students were actually able to rent a rickshaw for the day and visit each site with me. They were not enthused about my proposed running method. Our rickshaw tour helped orient them to the very disorienting Kumbh area, and they also assisted with several hundred patient entries at the busy sectors 11 and 12. The dust and poor roads seemed to get the best of a couple of them, but overall they are very excited to be on board.”

Ahmed’s diary:

“It’s been 24 hours of alot of travel and dust. We started off from Lucknow in the train, only an hour late. Great journey. Kind of gave us the idea of the general infrastructure and health conditions that we were heading into. Allahabad at 10pm and 9°C. The owners of the place picked us up as they promised earlier, although I don’t remember them mentioning they’re gonna be drunk while they do it. The place is fabulous. Great rooms. Great bathrooms. But….. No water heater. Every time we touch water, it’s like the limb might fall off. Luckily I carried a heating coil, the services of which I’m offering to my team members in return for rent free stay over these fifteen days. The matter is under negotiations. Aaron was super nice to come by and meet us late night just after we arrived. It was great to get oriented the night itself. We downloaded the EMcounter application and had a short demo of how it’s used . He’s made a great network of people who help him get around places. Not that he needs them to do it.

Next morning:

We hired a 6 seater rickshaw for Aaron to show us around the entire Kumbh site and the medical facilities. The medical facilities are great. They’ve got great inpatient wards, some would say, even better than the ones we have in established tertiary care hospitals.

This is how we work:

The doctors are required to keep a record of all patients and medicines administered. This register, has poorly recorded data. We borrow the register from the day before and feed it into the application. We are in the process of getting a signed and stamped letter from the highest health authority of the Kumbh”

The rickshaws didn’t last long. Boys will be boys. And soon, the team had rented a few scooters that they used to navigate the crowds and cows and Mahavir, Jagdish and Triveni Roads up and down the Kumbh Mela. Little by little, our fantastic team of students from across India were learning the principle of public health field research: tenacity, ingenuity, patience, persistence, improvisation, and innovation.

We left a week ago, but the project continues. This week the team met Rishi Madhok, another emergency physician from NYP, and the technical lead for EMcounter, who arrived in Allahabad a newly married man, straight from his honeymoon. Rishi will work with the local team to expand the survey to the Central Hospital in Sector 2 where we will capture a wholly different set of pathologies – sicker patients with more complex medical problems presented to the Central Hospital.

(Ghanshyam and Raunak learning to prepare serial dilutions)

We will remember our time at the Kumbh Mela fondly. The chanting, the smells, the music emanating from every street. The dense crowds on Mauni Amavasya. The millions that stood in waist deep waters and raised their palms to the sun as millions before them always have. It was spectacular. It was poetic. And it was profoundly humbling.

But interacting with our local team was equally, if not more, exhilarating. Reading Avnish’s policy recommendations for future Melas, following Abhishek on a tour of his hospital wards, listening to Aditi oscillate between psychiatry and pulmonology as her career choice, supporting Ahmed as he worried about the incoming team-mates that cancelled their tickets after the stampede, observing Aaron navigate his way around the Mela like he was strolling on the lower east side of Manhattan, and watching Ghanshyam engrossed over a tuberculin syringe dripping E.coli laden water onto a culture plate, we were reminded of our collective pursuit of knowledge — unfettered by age, gender, caste or creed.

At the world’s largest gathering of faith, we had bonded over science.

NY Times Blog on HSPH Project

Can Big Data From Epic Indian Pilgrimage Help Save Lives?

Big data, meet humanity.

The South Asia Institute at Harvard has sent a team of public health specialists to one of the largest gatherings in the world, the Kumbh Mela in India, with a goal of assembling the largest public health data set ever among a transient population.

The Kumbh Mela, a religious festival that is expected to draw nearly 100 million pilgrims, is in full swing … [READ MORE]

Waiting for an Uneventful Day

February 9, 2013:

The crowds in the Kumbh Nagri have swollen to fill the sandy Gangetic floodplain as the largest bathing day begins tomorrow. Today the roads brimmed with pilgrims on their way to and from the Sangam; the barricades rolled to block all vehicular traffic from entering the City. A great deal of attention has been paid to developing infrastructure that can both accommodate and control the movements of cars, lorries, rickshaws, bicycles, motorcyles, and millions of people.

The streets at the Kumbh Nagri are wider than those in most Indian cites. The major thoroughfares can easily hold four or five standard lanes of traffic. Although the road margins are periodically obstructed by celebrants lining up crossed-legged to receive Prasad or by the ubiquitous informal merchants displaying wares on ground cloths, there is no encroachment of the semi-permanent structures of the camps onto the road. The size and uniform width of these thoroughfares provide an ostensibly bottleneck-free area for the movements of people going to bathe at the Sangam.

At each major intersection moveable metal barricades manned by police can rapidly shunt the flow of traffic away from a particular area and generate unidirectional flow. These barricades typically control auto traffic only, but could in theory be used to move people away from a highly congested area with stampede potential.

Walking to the Sangam from the east bank of the Ganga one crosses the river on a dense network of pontoon bridges. Because the bridges are only wide enough for one lane of auto traffic flanked by two narrow sidewalks, major roads with bidirectional traffic split to traverse the river on 2-3 bridges each. A network of barricades and pikes control flow onto the bridges. Auto traffic is unidirectional but pedestrians so far are allowed to move in both directions. The bridges represent bottlenecks compared to the generous width of the roads. The western bank of the Ganga has a flat and gradual slope but the eastern bank is a 10-20 foot escarpment of sand that drops abruptly into deep and fast moving water. There is obvious potential for drowning in the event of a stampede. Post and rail fences and cuts through the earth of the embankment that funnel the crowds onto the bridges attempt to mitigate the dangers posed by these natural obstacles.

At the heart of the Sangam on the west bank of the Ganga, the land gently slopes into the water. As one nears the bank, straw blankets the ground for approximately 30 meters to provide traction for millions of wet feet as they return from the holy waters. Getting nearer the water, the straw gives way to sandbags lining the river’s edge for 1-3 meters for the length of the major bathing areas. The sandbags are placed to prevent erosion and stabilize the bank, but they also have the effect of solidifying the sand for the crush of people waiting their turn to enter the water.

The river currents are treacherous, swift and changeable as the Ganga merges with the Yamuna and the water deepens precipitously as one walks from the water’s edge into the depths of the river. Periodically positioned spurs of sandbags serve to break the swift current into safer eddies for the bathers. Poles sunk into the mud and connected by cordons demarcate the deep water where hired rescue boats bob in a state of constant alertness.

Outside one of the main entrances into the Kumbh, where city roads meet Nagri roads, crowds are to be diverted into a massive corral spread over five to seven acres, where they will be encouraged to follow winding paths demarcated by bamboo fences. Some locals fear that the visitors may simply jump through the fences and attempt to cut straight through the field.

All roads leading to the Mela, and for several kilometers around, have been shut to vehicular traffic. The paths to the Sangam are packed, the bridges are full, and the sidewalks lined with sleeping pilgrims. Millions will soon descend upon the confluence for their holy bath. The atmosphere in the administrative offices is tense. The wide roads, the winding corrals, the sturdy bridges, the sandbag spurs, the rescue boats and the mounted police are in a heightened state of readiness. Long months of deliberations, design and implementation have been invested to make this one day as uneventful as possible – as uneventful as the world’s largest human gathering can be.

Michael Vortmann

FXB Team Back at the Mela

February 5th

Today, the second team from the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights arrived at the Kumbh Nagri to continue to study the public health implications of the Kumbh Mela. The public health team that visited the Mela along with the rest of the Harvard contingent in January had initiated a disease surveillance system at the sector hospitals serving the pilgrims visiting the Kumbh. This ambitious undertaking piloted at four of the 10 sector hospitals hopes to capture, in real time, the epidemiology of diseases presenting at the healthcare facilities at the Kumbh Mela. The project is implemented locally by a large network of medical students from across India, who, for the past several weeks, have been diligently recording data from patient registries into their iPads. Navigating bumpy roads, traffic jams, long distances, inclement weather, and reticent physicians (sometimes enthusiastic, often times reluctant, and always overworked), our medical students are having “a time of their life.” They said so themselves – over chai and halva – as we exchanged notes against the tintinnabulation of the evening’s aartis rising simultaneously from the many akharas beyond our fence.

We met with Aaron, Ahmed, Ghanshyam, Raunaq, Aditi and Shrunjal. After a 10-hour work day, a stalled motorcycle, and a 10 kilometer walk, they looked upbeat, excited, and were bubbling with ideas. Most of them are on the cusp of graduating from medical college, having just passed their boards, or about to take them. Their interests are diverse, ranging from psychiatry to critical care, yet what brings them here is a spirit of adventure and a commitment to service. “I would never have thought of coming to the Kumbh, were it not for this project,” said Shrunjal, “and I am glad I did.” They did not all know each other before this trip, and now they have learned to share a heating coil to heat up their bath water, learned how many snooze alarms it takes them to get out of their beds in the morning, and learned how to cajole the overworked physicians at the sector hospitals to write more legibly. Aaron, the New Yorker amongst them, and supervisor-at-large, has the best local sense of direction.

This evening, after settling into our rather comfortable tents perched on a small hill overlooking the Nagri (as had several members of this team, in the weeks preceding us), we walked over to the observation patio that overlooked the Sangam. I had visited the Nagri in the early days of December when it was under construction: endless rows of lusterless electricity poles marked a grid on the shifting banks of the Ganga, a few saffron flags fluttered impatiently in the evening breeze, important looking jeeps circled the empty plots unable to decide on a final location to pitch camp, and the final pontoons were being lowered into the water on the far-side. I had imagined what it would be like once the Mela started: saffron robed sadhus, pious pilgrims, loud chanting, incense, beads, flowers, and the holy dips. But I had imagined it in the light. This evening, I saw it in the dark.

From where I stood, all I could see – for as far as I could see – was a sea of golden lights, a million Diwali lamps lighting up the world’s largest fair.

Tomorrow, our team informs us, is an important bathing day: Ekadashi Snaan. Roads may be blocked, and millions may throng to the banks for a holy dip. Unfazed, we plan to venture out to visit the sector hospitals, the fruits of our teams’ labor in hand. The diligent work done by the medical students from Allahabad, Mumbai, Nagpur (and New York and Boston) has allowed us to create daily graphs of the frequency of medical complaints or diagnoses presenting to the hospitals under study. Tracking the frequency of diseases over time will allow us to understand and question deviations from the expected trends. Does an acute rise in incidence indicate a jump in the population or does it portend an epidemic? Can outbreaks be predicted in this setting before they occur? What ailments does this population most suffer from? Is some part of the burden of disease preventable? Tomorrow, we will present our analyses to local physicians hoping that they may pause and reflect on the enormity of their contribution. In ten days, over 12,000 patients have passed through four sector hospitals, as many diagnoses have been made, and over 15,000 medications have been dispensed.

The questions compete in number only with the bustling hordes of Kalpavasis coming to the Nagri: Who protects the health of this population? How effective is the water purification? How effective are the pit latrines? How is the sewage treated? What if there is an outbreak? What about the children? Where do they go if they are lost? Who cares for them? How are they found? Are they found? What about the elderly? The infirm? What if there is a stampede? A fire? A collapse?

The list is long, our time is short, but the opportunity to ask and answer, to seek and find, is priceless – as is the rhythmic beat of distant dumroos rising from the valley as they now lull our jet-lagged souls to sleep.

Tomorrow, will be our first day at the Kumbh Mela. Tomorrow we will see the Sangam.